X-rays uncover a hidden property that leads to failure in a lithium-ion battery material

Experiments at SLAC and Berkeley Lab uproot long-held assumptions and will inform future battery design.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Over the past three decades, lithium-ion batteries, rechargeable batteries that move lithium ions back and forth to charge and discharge, have enabled smaller devices that juice up faster and last longer.

Now, X-ray experiments at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have revealed that the pathways lithium ions take through a common battery material are more complex than previously thought. The results correct more than two decades worth of assumptions about the material and will help improve battery design, potentially leading to a new generation of lithium-ion batteries.

An international team of researchers, led by William Chueh, a faculty scientist at SLAC’s Stanford Institute for Materials & Energy Sciences and a Stanford materials science professor, published these findings today in Nature Materials.

“Before, it was kind of like a black box,” said Martin Bazant, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and another leader of the study. “You could see that the material worked pretty well and certain additives seemed to help, but you couldn’t tell exactly where the lithium ions go in every step of the process. You could only try to develop a theory and work backwards from measurements. With new instruments and measurement techniques, we’re starting to have a more rigorous scientific understanding of how these things actually work.”

The ‘popcorn effect’

Anyone who has ridden in an electric bus, worked with a power tool or used a cordless vacuum has likely reaped the benefits of the battery material they studied, lithium iron phosphate. It can also be used for the start-stop feature in cars with internal combustion engines and storage for wind and solar power in electrical grids. Better understanding of this material and others like it could lead to faster-charging, longer-lasting and more durable batteries. But until recently, researchers could only guess at the mechanisms that allow it to work.

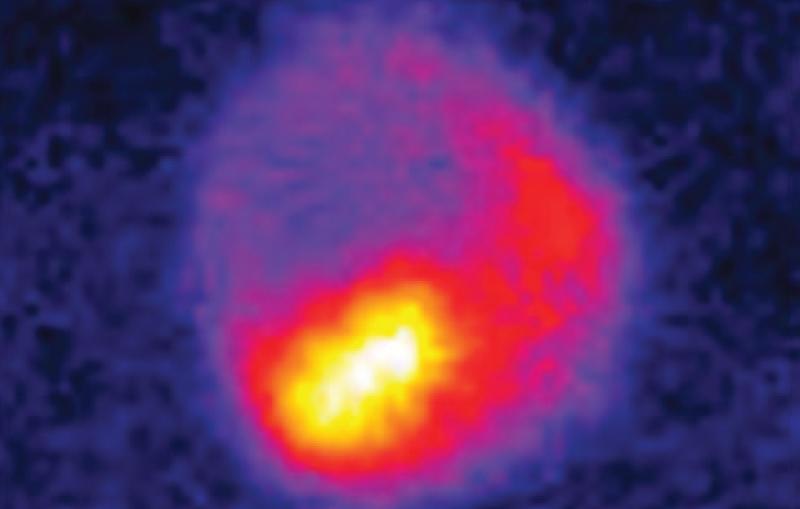

When lithium-ion batteries charge and discharge, the lithium ions flow from a liquid solution into a solid reservoir. But once in the solid, the lithium can rearrange itself, sometimes causing the material to split into two distinct phases, much as oil and water separate when mixed together. This causes what Chueh refers to as a “popcorn effect.” The ions clump together into hot spots that end up shortening the battery lifetime.

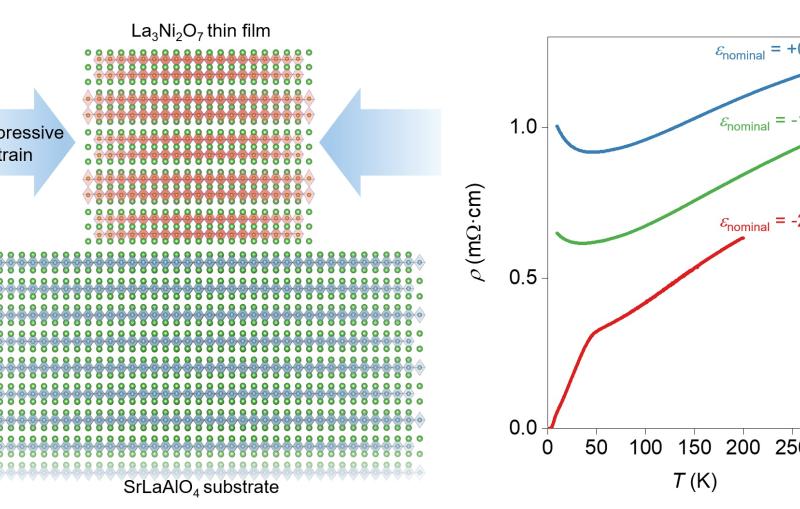

In this study, researchers used two X-ray techniques to explore the inner workings of lithium-ion batteries. At SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) they bounced X-rays off a sample of lithium iron phosphate to reveal its atomic and electronic structure, giving them a sense of how the lithium ions were moving about in the material. At Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source (ALS), they used X-ray microscopy to magnify the process, allowing them to map how the concentration of lithium changes over time.

Swimming upstream

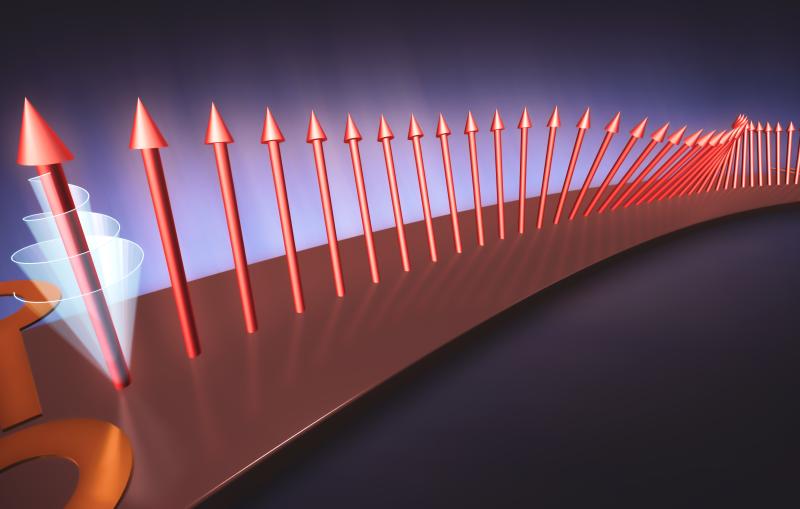

Previously, researchers thought that lithium iron phosphate was a one-dimensional conductor, meaning lithium ions are only able to travel in one direction through the bulk of the material, like salmon swimming upstream.

But while sifting through their data, the researchers noticed that lithium was moving in a completely different direction on the surface of the material than one would expect based on previous models. It was as if someone had tossed a leaf onto the surface of the stream and discovered that the water was flowing in a completely different direction than the swimming salmon.

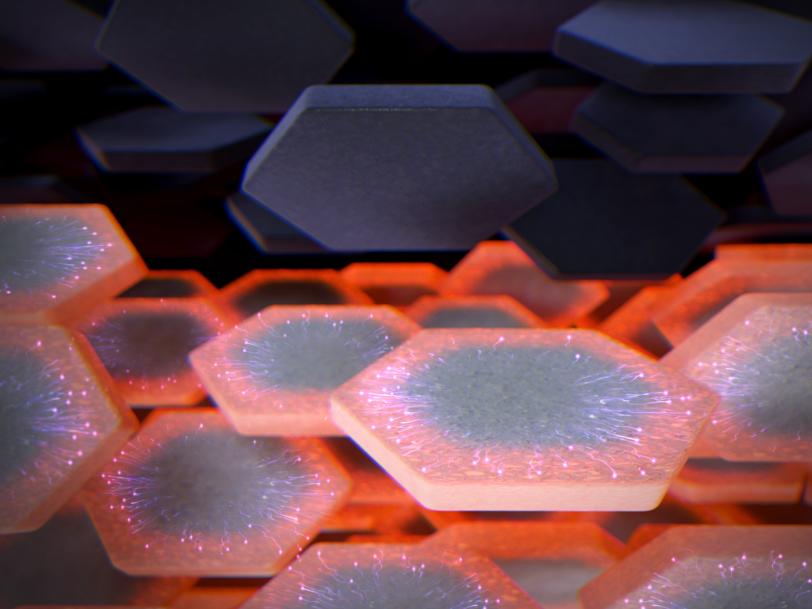

They worked with Saiful Islam, a chemistry professor at the University of Bath, UK, to develop computer models and simulations of the system. Those revealed that lithium ions moved in two additional directions on the surface of the material, making lithium iron phosphate a three-dimensional conductor.

“As it turns out, these extra pathways are problematic for the material, promoting the popcorn-like behavior that leads to its failure,” Chueh said. “If lithium can be made to move more slowly on the surface, it will make the battery much more uniform. This is the key to developing higher performance and longer lasting batteries.”

A new frontier in battery engineering

Even though lithium iron phosphate has been around for the past two decades, the ability to study it at the nanoscale and during battery operation wasn't possible until just a couple of years ago.

“This explains how such a crucial property of the material has gone unnoticed for so long,” said Yiyang Li, who led the experimental work as a graduate student and postdoctoral fellow at Stanford and SLAC. “With new technologies, there are always new and interesting properties to be discovered about materials that make you think about them a little differently.”

This work is one of the first papers to come out of a collaboration between Bazant, Chueh and several other scientists as part of a Toyota Research Institute-funded research center that utilizes theory and machine learning to design and interpret advanced experiments.

These most recent findings, Bazant said, create a more complex story that theorists and engineers are going to have to consider in future work.

“It further builds the argument that engineering the surfaces of lithium-ion batteries is really the new frontier,” he said. “We have already discovered and developed some of the best bulk materials. And we’ve seen that lithium-ion batteries are still progressing at a pretty remarkable pace: They keep getting better and better. This research is enabling the steady advancement of a tried technology that actually works. We’re building on an important bit of knowledge that can be added to the toolkit of battery engineers as they try to develop better materials.”

Spanning different scales

To follow up on this study, the researchers will continue to combine modeling, simulation and experiments to try to understand fundamental questions about battery performance at many different length and time scales with facilities such as SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source, or LCLS, where researchers will be able to probe single ionic hops that happen at timescales as fast as one trillionth of a second.

“One of the roadblocks to developing lithium-ion battery technologies is the huge span of length and time scales involved,” Chueh said. “Key processes can happen in a split second or over many years. The path forward requires mapping these processes at lengths that go from meters all the way down to the motion of atoms. At SLAC, we're studying battery materials at all of these scales. Combining that with modeling and experiment is really what made this understanding possible.”

In addition to SLAC, Stanford, Berkeley Lab, MIT, and the University of Bath, the collaboration includes researchers from the National Institute of Chemistry and the University of Ljubljana, both in Slovenia.

LCLS, SSRL, and ALS are DOE Office of Science user facilities. The theoretical aspect of the work was supported by Toyota Research Institute, among other funding agencies.

-Written by Ali Sundermier

Citation: Li et al., Nature Materials, October 17 2018 (10.1038/s41563-018-0168-4)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.